Contents:

-

Auxiliary power system sizing – Solar

-

Re-Engining a Moody 425

-

Removing and inspecting the Rudder

-

Replacing the Steering Cables

-

Steering system maintenence

Auxiliary power system sizing – Solar

Vega has been lucky enough to have a power supply on her home jetty for the past few years and has only enjoyed short weekend coastal passages. As a result she has non of the auxillary charging systems often associated with offshore or cruising yachts. We need to fix that. Where we plan to go, it will be very useful to not need to connect to mains power or run the engine on a regular basis (even though in the Med we probably will…) so we are looking at solar and wind as options. Hydro is also an option, but it is very expensive and generally the domain of major sponsored offshore racing yachts.

In assessing what kind of set up we need, the first step is to work out approximately how much power we will use on a typical day. Here is our guestimate based on either coastal cruising or passage making:

Clearly these calculations are subjective, but we have benchmarked the consumption from a number of different sources so it should represent a reasonable start.

Vega currently has four gel batteries installed in 2013 that are in good condition, so we are reluctant to change them. The batteries are all identical so that they can be swapped around and charged together easily. They are all rated at 130Ah. Only two are available to serve the power loads calculated above as one is dedicated to the engine and another to the bow thrusters and windlass.

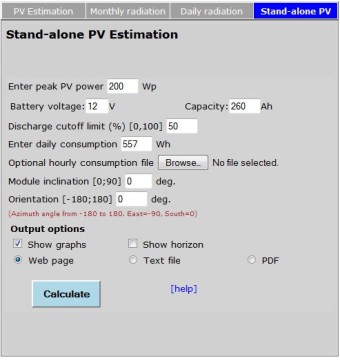

How many panels do we need to support our consumption? The EU has released a fantastic solar calculator which allows us to get an idea of how many solar panels would be required to provide enough power to meet our needs. Here is a screen shot of our inputs to estimate the panel size to manage our coastal cruising consumption.

We’ve assumed that to enhance the life of the batteries we would never want to discharge them to less than 50% capacity. We’ve also based the calculations on an area of average solar insolation for the Mediterranean (East coast of Sardinia) and that the panels are installed flat (assumed to be on a radar arch that we still need to build).

We would like the solar panels to initailly meet all our coastal cruising requirements from April – September. The power input from the engine will be a bonus and will hopefully offset any loses from shading by the boom, sails, backstay etc. Using the EU’s Photovoltaic Geographical Information System we were able to work out the percentage of days that our battery bank would be fully charged and fully discharged for different solar array peak output ratings. The graph below shows that we would need a solar array rated at at least 200Wp to meet our average coastal cruising daily power demands. Clearly this is based on peak loads and includes a bunch of assumptions, but it should be a good starting point.

Installing a new Engine

When we purchased Vega, she was 25 years old. So was her engine. Now don’t get me wrong, there are plenty of 25 year old engines knocking around, but i have learnt that old engines can be fickle…very fickle. One minute they are fine, the next..well they are not. When they are sick, the bills can mount rapidly as can the time spend diagnosing intermittent faults. As the bills mount up it can be hard to cut your losses as you have invested so much in to the old donkey.

Vega’s original engine was a Thorneycroft T98 Diesel Engine, essentially a marinised version of the Ford XLD1600 42hp car engine. Very reliable – and the base engine is well proven and tried and tested. Spares are still around, but are getting increasingly hard to source. Our engine seemed in reasonable shape even if she shook and vibrated a bit, However, she needed plenty of TLC and we had no records for her hours or maintenence history.

We had a decision to make. Take a chance on her and if things went south put up and shut up accepting we may end up spending extended period’s in port fixing issues or replace her with a new generation, fuel efficient engine. We umed and are’d for a long time…a new engine is an expensive proposition. we looked at a whole range of engines, Beta, Yanmar, Vetus, Sole etc

What Horse Power?

We found it difficult getting clear data on the engine Horse Power that would be suitable for our yacht. But we came across a host of imperial data and rule thumb…

The Westerbeke Corporation suggests 2 hp for every 1,000 lb of displacement for coastal cruising, and 2.5 hp per 1,000 lb of displacement for offshore work. Vega displaces approx. 22000 lbs, that would mean 40Hp for coastal cruising and 55Hp for Offshore use.

In their book “The Gougeon Brothers on Boat Construction” the authors suggest a good rule-of-thumb is 1 hp for every 500 lb of displacement… that would mean a displacement of 22000lbs a 44 Hp engine should be suitable.

Other sources referenced 3 – 5 hp (continuous rating) per long ton … that would mean a boat with a displacement of 22,000 lb should have a 30 – 50 hp engine. For offshore conditions some people suggest the engine be larger than the size calculated for coastal cruising, possibly + 25%… so in this example the engine size would be increased to 60hp at the upper end.

So, based on a bunch of research and discussions with various suppliers it seemed that 40-60Hp was the right kind of size. We went with 50 HP. It seemed that once you had an engine of broadly the right horse power, the matching of the prop the the engine was of more real importance than the overall hp.

Retro Fitting

Non of the new engines on the market would fit on the original engine mounts. The width of the mounts was fine. The issue was in relation the the depth of the sump. The modern sumps were deeper and therefore our mounts had to be raised up. This was done with the fabrication of a pair of steel rails which sat onto of the original mounts, raising the engine up.

What Engine?

Yanmar and Volvo are probably the two most prevalent makes. We had a yanmar 3GM30 in our beneteau and it was not a bad engine, but with only light use ( 950 total hrs) we had issues relating to the exhaust elbow, water ingress to the cylinders, air intake and engine mounts. Replacement parts were very expensive. I understand Volvo parts are equally pricy. We Settled on the Beta 50Hp. They are british made and have an excellent reputation – they have been developed from a Kubota engine which is used extensively in heavy machinery such as forklifts and heavy duty generators where they can run for hundreds of thousands of hours!

The Beta seemed to fit many of our requirements, we could afford it and it had been installed in a number of similar yachts. We purchased the engine through TS Marine in the UK who also offered an installation and commissioninpackage (in Spain). The cost of the whole installation was just over 12,000GBP. Including Engine, 130 amp alternator, new engine mounts, new shaft, prop and PSS Seal. It also covered a host of other incidentals during the installation.

Was it the right choice?

Heather and i can disagree on lots of things..but on the new engine, we both agree it was the the right choice. I am aware of at least two Moody’s with old engines that packed in this season. From the outset, we had piece of mind when cruising, and when cruising with a young family, that was important to us. Once or twice we had to punch into 40 knots and a decent sharp wave set and the moody/beta combination worked a treat. Cruising at 7.5 knots if we need to we can get places quickly too 🙂

Dropping our Rudder

Our pre purchase survey noted high moisture readings in the rudder and a “dull” return from the hammer test. So we decided to drop the rudder to inspect the rudder integrity, shaft, O-rings and bearings. Our rudder turned out to be in great condition, but the same couldn’t be said for our quadrant and this turned out to be a bigger job than anticipated. Don’t they all….

Dropping the rudder was reasonably straightforward. There were only two complications. The first was removing the four bolts securing the quadrant around the shaft. These were stainless steel bolts passing through the aluminum quadrant casting, and over time they had corroded to the point they wouldn’t budge. Finally, two of the bolts needed to be cut off. Removing the cable attachment points was also problematic, but in the end they came out in one piece and were reusable.

The second issue was removing the bronze shoe from the base of the rudder skeg. The shoe is attached to the Skeg with ½” diameter copper rivets. The only way to remove them is to grind the heads off one side and knock them out. This is straightforward once you get your mind around taking an angle grinder to your rudder skeg…not something we have done before.

The biggest problem in the whole disassembly was the discovery of two cracks in the quadrant. One major crack and a secondary hairline fracture. Both cracks were in the part of the quadrant that sits “behind” the rudderstock and it looked like they could have been caused by over tightening of the quadrant bolts. Anyway, scary stuff…the Vega had probably been sailed this way for a while. We looked into getting a replacement part made at a machine shop in figures, the nearest large town to Emporiabrava but at an initial estimate of 975 Euro, we decided otherwise.

Sourcing the new Quadrant

After after research including Edison, Lewmar and Jefa Quadrants, we settled on a new Jefa Quadrant. Made out of High Strength 6028 Aluminum, they looked solid and their lead time was minimal. Plus, the Jefa team seemed genuinely keen to help and were very easy to deal with.

Prices of all manufactures were, as you may expect similar, around 800 Euro for a new quadrant, but Jefa could deliver the whole quadrant to Spain within a week of us supplying the drawing!

Lewmar, on the other hand, quoted us a month to deliver, but couldn’t even guarantee it would be there in a month.

Sizing the Quadrant

The Radius of our original Quadrant was 375mm. Jefa made off the shelf units in 350mm and 400mm radi. The 400 was to big and the 350mm would have required the cable guide to have been packed out, not a huge job, but still one more to contend with. As it turned out the bespoke quadrants from Jefa were the same price as the off the shelf ones. So we ordered a 375mm quadrant.

When getting a quadrant manufactured you need to take care to measure all the critical dimensions very accurately – these include overall quadrant general arrangement dimensions, stock/quadrant key dimensions, rudder stop extents and locations and of course the stock diameter.

We got hold of vernier calipers (called “Pies el Rey” in Spanish, which translates as the Feet of the king!!). With all our measurements Heather produced a sketch up 3D model of the quadrant and emailed it off to Jefa In Denmark. Over 24 hours we spoke to Jefa four times about the dimensions including clarifications on the rudder stops and autopilot attachment.

Through the entire process, Jefa were an absolute pleasure to deal with and within 5 days from initial contact we were delivered a new quadrant. It looked great.

Did it fit? In a word, no….

We were not quite as accurate as we should have been with the quadrant/stock key slot dimension. But we had erred on the tight rather than slack side so all that was required was a little filing of the key slot so it fitted well.

The quadrant has to fit onto the stock at just the right height so that the outer edge of the quadrant aligned with the cable guide. When fitted so as to align the outer edge of the quadrant (the part the cables run in) to the cable guide we found that the quadrant was right at the top of the stock, in fact the top face of the quadrant boss was a few mm above the top of the stock, which wasn’t good. We fitted the quadrant “upside down” and she was a much better fit.

However, fitting the quadrant upside down meant that our auto pilot attachment was now on the upper face of the quadrant, resulting in the auto pilot attaching to the the quadrant at an angle of 12 deg. to the horizontal. The Autohelm manual gave a strict warning that the arm must be within 5 deg. of horizontal. So we had the auto pilot attachment block removed and re welded on the underside of the quadrant – this bought the auto helm arm back to 5.5 deg. which I took to be ok.

Once the autopilot issue was resolved and the key slot filed to suit, the whole process of re assembly was straightforward.

Re – Installation of the Rudder.

Our rudder was thoroughly inspected and was given a clean bill of health. Our rudder bearings were in great condition, but the O- Rings were misshapen and perished so we replaced them with new.

Before we could reinstall the rudder we needed to locate ourselves some new 0.5 inch dia copper rivits to hold the bronze shoe to the skeg. The bronze shoe they fit to the stock is curved in both planes towards the bow, which means that all the rivits are different lengths.

Sourcing 0.5 inch dia copper rod in Spain proved impossible (unless I wanted to purchase a 6m long bar…) so my dad came to the rescue in the UK where he bought bar which was slightly oversized and turned it down on his lathe so that each rivet had a head on one end. He then bought these to Spain and they fitted perfectly. You need to make sure you leave at least a length equal to the dia of the rod to allow sufficient material to peen over to form the head of the rivet, then using 2 people, you will need one holding a large hammer on one side of the rod while you peen the other with a ball hammer.

The rivits in place through the shoe we had to peen the headless ends of the rivits so they wouldn’t come out. This took quite a bit of work, and as you peen the copper it work hardens so you need to get it right to prevent too much hammering.

The end result was great and we were very pleased with our efforts and had learnt a whole host of new skills! Great Result.

Replacing Vega’s steering cables

Vega’s steering had as always felt a bit tight. Over the years a number of moody owners had said that replacing the cables, and the conduits would make a difference. So, we decided to give it a go. We bought a new kit of parts including new 8mm steering cable and all new conduit and sheave attachments from a fella called Cliff in the UK at www.yachtsteeringservices.com

The kit looks like this:

The quality of the cable and chain components is excellent, but I wasn’t super happy with the new conduit end connectors (the black parts in the above picture) they are moulded plastic and the stainless nuts that thread onto them had a habit of cross threading really easily. The original brass compression fittings (see photo below) provided by Moody seem much more heavy duty. I would have reused them if I could, but the new blue conduit had a rib in it meaning it couldn’t be used with the original fittings.

The Moody 425 is a centre cockpit yacht, so the cables run from the pedestal, through the engine bay under the cockpit and then run under the aft cabin floor and aft bunk onto the rudder quadrant, in the aft lazarette. All up there is just over 10m of conduit and slightly more cable. The conduit that passed through the engine bay was not in good condition. It was discoloured and cracked in a number of locations.

Removing the existing system

Detaching the existing cables from the quadrant was straightforward. We had fitted a new quadrant in 2014 and all the connections were coated in duralac so there was no corrosion. With the cables undone at the quadrant end, we removed the binnical at the top of the pedestal in the cockpit and pulled the steering chain up off its sprocket and continued to pull the cables out of the conduit and into the cockpit.

As we pulled them out they were accompanied by a white dust. This was what reamied of the grease between the conduit and cable – the heat in the engine bay and the craked conduit had caused it to dry out introducing friction into the system. Not great.

Upon removal and closer inspection, the cables themselves appeared to be in great condition no obvious damage or faying to be seen anywhere. Not bad when you consider they were installed in 1989. So, with the cables out…next was the conduit.

This was the hard bit. The conduit comes in two lengths – from the underside of the pedestal to the top of a 90 degree sheath in the engine bay and then on from the underside of this sheath to a plate on the wall of the aft lazarette the just before the quadrant. At each of these terminals were the brass compresson fittings that effectively clamped the conduit into the fitting.

These hadn’t been loosened in over 25 years and were hard to remove. Once they’re removed we also had to remove the threaded fittings they were attached to. This proved very hard. In fact the two at the base of the pedestal couldn’t be budged and as we applied more and more force, we were worried about cracking the aluminium pedestal casting. So we gave up and left them in place. This meant that we couldn’t use the new conduit, but the original aft sections of conduit were in good condition so we ended up cutting these to length and reusing them in the engine bay. Eventually we removed all the conduit and re installation could begin.

Reinstallation.

Apart from difficulties cutting the new conduit – its stainless steel sheathing is incredibly tough and our hacksaw very blunt and the difficulty of working in confined spaces the reinstallation of the new conduit was really quite straightforward. We regularly inspect the quadrant and cables so reconnecting them was straightforward too.

So what did we get:

- All new cables.

- New conduit through two thirds of the system.

- Recycled original conduit over one third of the system.

- We also got new cable/chain connections (we opted not to replace the chain – ours looked to be in excellent condition).

- The whole system is greased and we understand it a whole lot better.

- Also….our steering is now a whole lot freer and the wheel much lighter to use. Great result.

It took a whole weekend – but its time well spent.

It was a messy job..but well worth it.

Steering System maintenance

If you are interested, there is a great article on steering system maintenance, from Ocean navigator:

http://www.oceannavigator.com/Ocean-Voyager-2015/Steering-inspections-for-the-offshore-boat/

Check it out – very informative and well worth a read.

Dear all,

Let me introcude myself. My name is Diana Kulchitskaya and I am a freelance journalist. Currently I am helping a Russian site about sailing create content. They are looking for stories about trips to the Mediterranian. The site is sailroad.ru

I spotted your blog and decided to write to you. Would you agree to give the permission to publish some of your posts on the Russian web-site? There will be a credit, saying the content belongs to you and it is translated from English to Russian.

Thanks in advance!

Sincerely,

Diana.

LikeLike

Hi Diana, No problem…provide a link to ayachtmoretolife, so they can check out the site too.

Regards

Richard

LikeLike

Hi guys, thanks for sharing your engine story. We are in the boat market and looking at similar boats with or without new engines. Your post is super helpful. Hope to see you on the water sometime! Lynita Castadrift.com.au

LikeLike

Hi Lynita, glad you found it useful 🙂 what sort of boat are you looking for?? Are you based in Australia? Rich

LikeLike

Rich, Australians currently in Europe and zeroing in on Moody or Oyster 44ish ft. Hope to see you on the water sometime! Love your website. (We are http://www.castadrift.com.au)

LikeLike

Great post thanks heaps for telling me about it. Do you find your batteries are enough for your usage? What kind of solar panels did you get in the end? Thanks heaps

LikeLike

Sorry for the delay in replying – Rich needed his technical officer to reply and I’m not an easy person to pin down to a computer. We have 2 x 130Ah AGM batteries – this year they don’t seem to be holding their charge as well but they are now about 5 years old. I reckon that we are down to 130Ah capacity and considering we only want to drain to 50% capacity, we only have around 60Ah of storage left – time for new batteries soon. We have been absolutely fine all season while the sun is shining but can not get through an overcast couple of days without running the engine. Luckily in the Med, clouds are few and far between. We ended up getting 2 x 80W polycrystalline panels made by Viltron. We also have a Viltron MPPT controller. We have found that in terms of usage – all the estimates have been fairly accurate, only underestimate was the autopilot. In big seas it can draw 7-8 Amps so after a night passage under sail with the autopilot, particularly later in the season (with fewer daylight hours), the batteries are desperate for a top up by morning. Might be time for a new, efficient autopilot as well 🙂

Heather

LikeLike